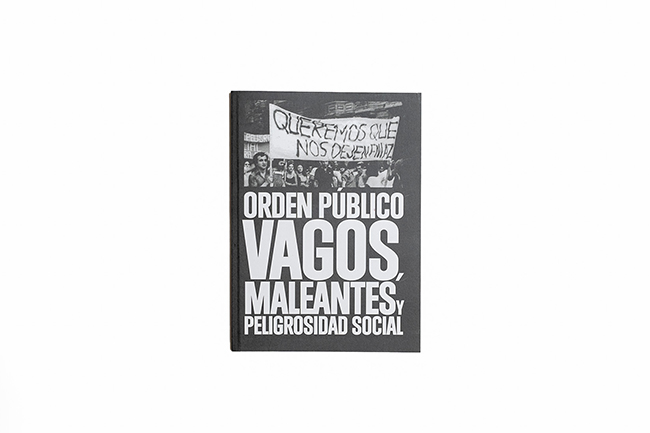

Orden público: Vagos, Maleantes y Peligrosidad Social Exhibition

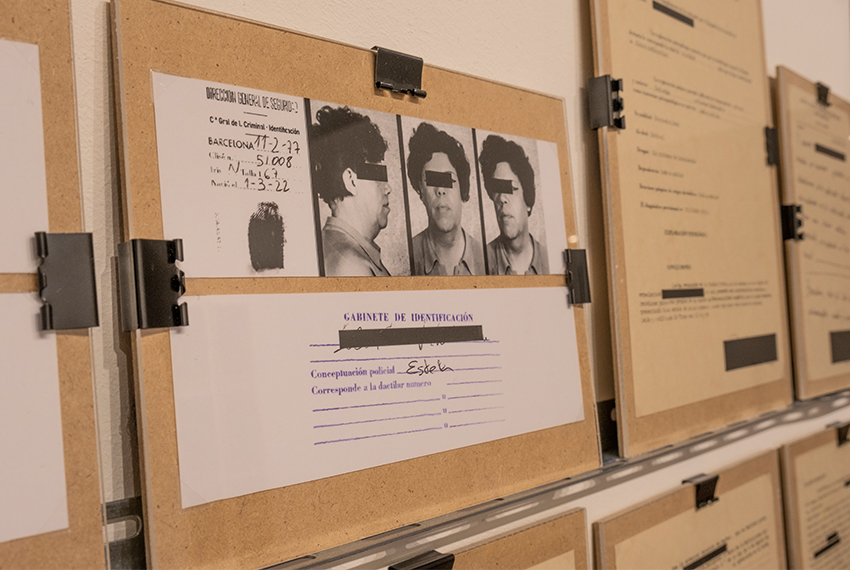

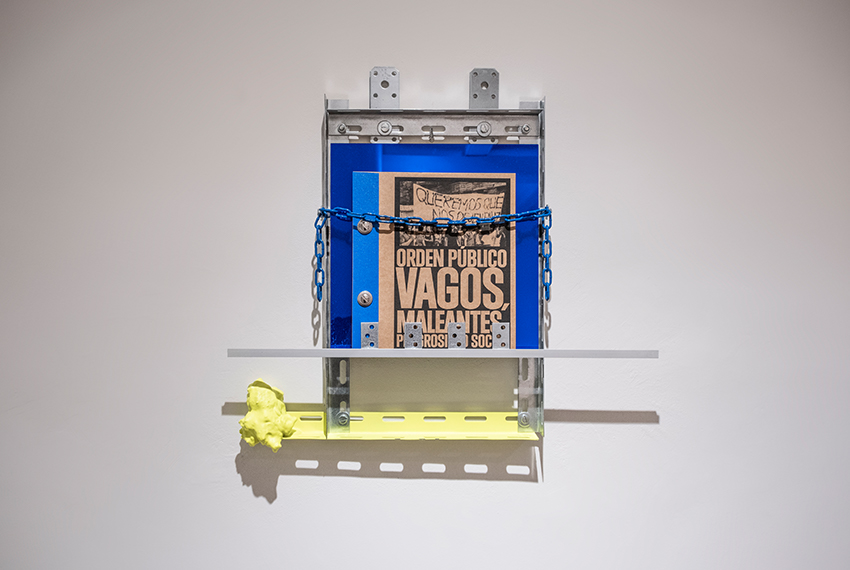

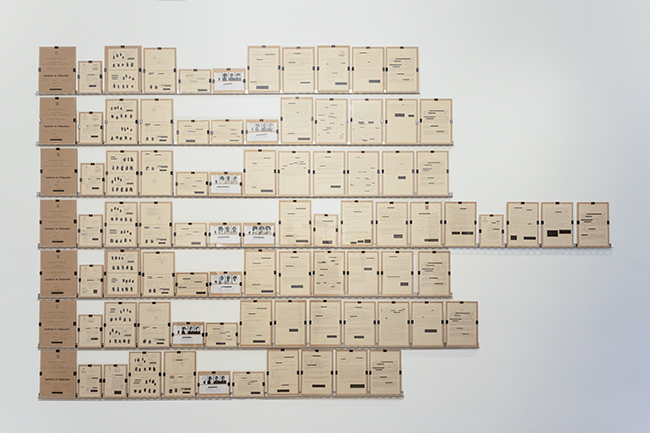

“Orden público: Vagos, Maleantes y Peligrosidad Social” is a project by Daniel Gasol that smuggles files from the Vagos y Maleantes Act (1933-1970) and the Social Dangerousness Act (1970-1995) to think about how the legislation turns the underprivileged classes into criminals who must redeem themselves by working for the state.

When

1 December - 5 February 20221 December 2021 5 February 2022 Tuesday to Friday: 12 am – 8 pm Saturday: 11 am – 3 pm

Where

Chiquita Room- Este evento ha pasado.

Book your tickets for Orden público: Vagos, Maleantes y Peligrosidad Social

1 December - 5 February 2022

Tuesday to Friday

12 am – 8 pm

Saturday

11 am – 3 pm

Book now

ACTIVITIES

Opening

Wednesday, 1 December 2021 at 19h.

Guided tour of the exhibition by the artist

Wednesday, 15 December 2021 from 7 to 8 p.m.

Chiquita Room. Villarroel, 25. Barcelona.

Free activity.

“Personal file: an essay on bureaucracy”

Thursday, 20 January 2022 from 7 to 8:30 p.m.

Gallery 4, La Modelo. Entença, 155. Barcelona.

Free workshop.

“Legislation and social rights”

Round table with Antoni Ruiz and Silvia Reyes, people linked to arrests for social dangerousness.

Thursday, 27 January 2022 from 7 to 8.30 p.m.

Gallery 4, La Modelo. Entença, 155. Barcelona.

Free activity.

Guided tour of the exhibition by the artist

Wednesday, 2 February 2022 from 7 to 8 p.m.

Chiquita Room. Villarroel, 25. Barcelona.

Free activity.

“Bums, Thugs and Social Dangers”

Celebrate life at El Cangrejo del Raval

Thursday, 3 February 2022 from 10 p.m. to 1 a.m.

Admission: 15 euros.

Guided visit to the exhibition by Daniel Gasol | Spanish

The social order is founded on the silence of almost everyone. The masters monopolise the word. And in the family, in the school, in the church, in the factory, in the hospital, in the barracks, in the prison, they inoculate us with the master’s word – half vaccine, half poison: a barrier against thought. Pact of silence. Times of change. Inheritance of an unresolved transition.

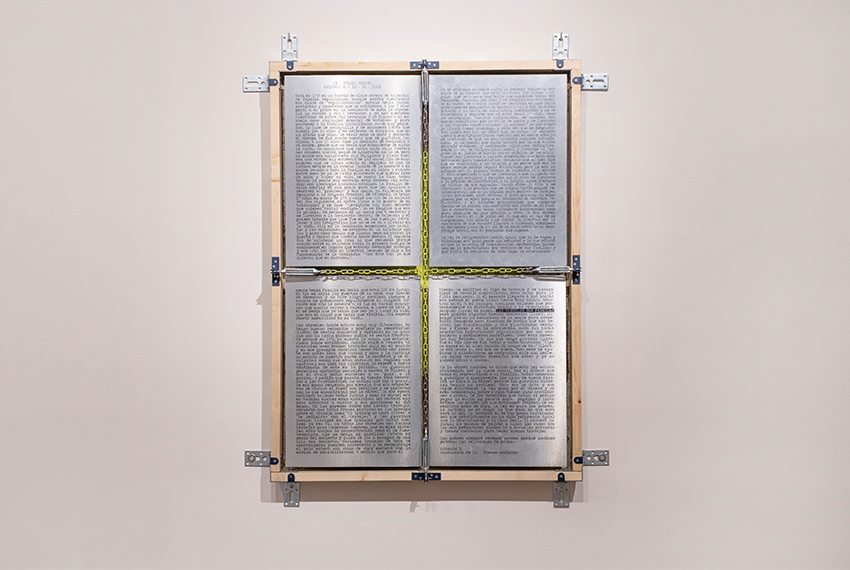

An individual subjected to examination leaves behind a documentary trail from which it will be difficult for him to free himself; on the contrary, this trail will constitute his biography, his individuality. The “history” of a person’s school, medical, military, police and judicial vicissitudes, etc., will shape him or her as a distinct subject. In this way, the results of the continuous examination make it possible to construct the individual subject (…) the examination turns the subject into a “case”, the object of knowledge and power. A subject who can be described and analysed and judged, but an individual who must be channelled, standardised and corrected.

He is making good progress. Needs to improve. Positive point. Two negative points. Surely those of us who were educated in the logic of what seemed to be a political transition have in these expressions the bitter memory of an education that continued to be constructed in a disciplinary manner. Rule and law. Surveillance and punishment. Or that under the guise of certain experiences of freedom continued to build structures and schemes that not only perpetuated the heteropatriarchal systems of the post-Francoist family, but which, in pursuit of that “progress properly”, advanced towards a welfare state that was none other than that of a covert liberalism that fell like a dark cloak over what the Madrid Pacts only left in the air.

“Vagos y maleantes” was an expression that hardly sounded familiar to many of us who were educated in the decade after Franco’s death. To the Spain of change, the Spain that was heading for an elephant in a china shop entry into the European Union, the Spain that signed the NATO pacts and lined up in line with the builders of the New World Order, these words were obstacles to that supposedly modern democracy. Self-censorship and internalised repression after many years of dictatorship and post-war. Amnesia and hooking up, disenchantment monkey, as Teresa Vilarós called it, which continued to be present in the cultural productions of the eighties, among pens, syringes and various syndromes. Vagrants and thugs, faggots and junkies, the new criminal subjects.

Vagrants and thugs. Vagabonds, nomads, pimps and other behaviours considered antisocial were the targets of this order approved by the Cortes of the Second Republic on 4 August 1933 and modified by Franco’s regime on 15 July 1954 to include the repression of homosexuals. A disciplinary regulation with which to regulate desires and bodies. Bodies of crime, repressed bodies, bodies of law, social bodies. A court martial for pleasure. Pleasure is judged because pleasure frightens them, homosexuality is judged because it is a way of obtaining it.

Almost a century has passed since the establishment of the so-called Vagrancy Law and part of that narrative persists, the ghosts of another time continue to walk among us, with new faces and names. Whoever, through sweetness or privilege, tries to mitigate or abolish rebellion, destroys for himself all possibilities of salvation. And no one can forgive the crime unless he is first guilty and condemned.

While the melancholic left continues to talk of progress and change, conservatism continues to revive the ghosts of the past in an impossible march backwards that places us in a real quagmire with no way out. Here and now, where silence breaks.

“Orden público: Vagos, Maleantes y Peligrosidad Social” is proposed as a reactualisation of those devices of normativisation and surveillance, performing the archive, altering the copy, bringing it to the present time, where it persists under new strategies of domination, those of a capitalism that imposes on us its logics of precarious survival.

Anna Tsing writes in The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, but what if – as I suggest – precarity is in fact the condition of our time; or to put it another way, what if our time is the ideal moment to perceive precarity; what if precarity, indeterminacy, and all that we conceive as trivial are at the heart of the systematicity we seek? Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable encounters transform us; we are not in control, not even of ourselves. Unable to rely on a stable community structure, we are thrown into a series of shifting assemblages that reconfigure us as well as our fellow human beings. We cannot rely on the status quo; everything is in constant fluctuation, including our ability to survive. Thinking in terms of precarity transforms social analysis. A precarious world is a world without teleology. Indeterminacy, the unplanned nature of time, is terrifying; but thinking in terms of precarity makes it clear that indeterminacy also makes life possible.

Jesús Alcaide

Independent curator and art critic

Artist

Daniel Gasol

Daniel Gasol is an artist and holds a PhD from the University of Barcelona (2015). His artistic practice revolves around mediation, critical pedagogy and collective dynamics. He questions dominant discourses constructed by the powers that be on identity, work, class or consumption that convert forms of fiction and/or reality. He began his career combining research and artistic production, investigating the mechanisms that constitute hegemonic narratives.

Discover more